Ebook subscription startup Oyster expands to iPad and opens to all; some stats from Scribd

“Netflix for ebooks” Oyster launched on iPad and opened up to everybody Wednesday; previously it had only been available on iPhone. Rival service Scribd also released some stats showing that most of its use is coming from iPad.

October 2013

Big-5 publisher Macmillan makes many more ebooks available to libraries

Big-5 publisher Macmillan makes many more ebooks available to libraries Big-5 publisher Macmillan, which had previously only made 1,200 ebooks available to libraries for lending, is now opening up its entire backlist of about 11,000 titles.

Librarian Who Struggled to Read as a Child Now Helps Others in Staten Island

From The New York Times:

Patricia Ann Kettles did not read her first book until she was 10. She knows what it is to struggle with the very act of reading, trying to make sense of words on a page long past an age when other children can polish off a thick Harry Potter or Twilight novel as quickly as a wedge of cake.

Now 40, at the library on Staten Island where she presides and where patrons know her fondly as “Miss Patty,” she talked recently about what it was like to be illiterate while others around her were devouring entire worlds.

“The family’s name for me is Patty Ann, and for the longest time when I wrote the name ‘Patricia,’ I thought I was writing ‘Patty Ann’ because I had memorized it,” she said. “I didn’t realize I was not writing my right name.”

Forced to repeat first grade and twice made to switch schools, she was so lost that she was in fourth grade before she conquered an entire book. “That was ‘Dear Mr. Henshaw,’ by Beverly Cleary,” Ms. Kettles said. “I remember, because I was so proud.”

Today she is the manager of the Port Richmond Library, which operates out of a stately brick edifice that Andrew Carnegie’s largess built a century ago on “one of the finest residence streets on Staten Island,” as the area was described in The Staten Islander of March 1905. There is a theater in the basement bestowed upon the library 74 years ago by the Work Projects Administration.

Neil Gaiman: Why our future depends on libraries, reading and daydreaming

And I am biased, obviously and enormously: I’m an author, often an author of fiction. I write for children and for adults. For about 30 years I have been earning my living though my words, mostly by making things up and writing them down. It is obviously in my interest for people to read, for them to read fiction, for libraries and librarians to exist and help foster a love of reading and places in which reading can occur.

Neil Gaimen!!

Libraries in Unlikely Places

…on horseback, in supermarkets, in vending machines, on burros, in Walmart stores, etc.

BookRiot has put together a list of unlikely locations for libraries.

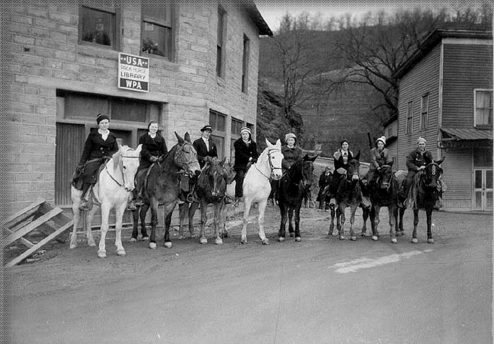

For example, here’s the pack horse library in Hindman Kentucky.

During the Great Depression, as part of an effort to boost employment for women, the Works Progress Administration funded the Pack Horse Library Project of Eastern Kentucky, which sent women out on horseback to deliver books to parts of the Cumberland Mountains inaccessible to cars and trucks. You can learn more about the Pack Horse Library and the women who made it possible in Kathi Appelt and Jeanne Cannella Schmitzer’s recently-released Down Cut Shin Creek: The Pack Horse Librarians of Kentucky (HarperCollins).

Open access: The true cost of science publishing

Open access: The true cost of science publishing

Although journal list prices have been rising faster than inflation, the prices that campus libraries actually pay to buy journals are generally hidden by the non-disclosure agreements that they sign. And the true costs that publishers incur to produce their journals are not widely known.

The past few years have seen a change, however. The number of open-access journals has risen steadily, in part because of funders’ views that papers based on publicly funded research should be free for anyone to read.

The End Of The Library

All of these prospects for the future of libraries sound nice on paper (figuratively, not literally, of course). But I’m also worried that some of us are kidding ourselves. These theoretical places are not libraries in the ways that any of us currently think of libraries.

That’s the thing: it seems that nearly everyone is actually in agreement that libraries, as we currently know them, are going away. But no one wants to admit it because calling for the end of libraries seems about as popular as the Dewey Decimal System.

An Ancient Library and Advice from the Buddha

Fascinating piece in the New Yorker about an ancient Chinese library in Dunhuang, unearthed about one hundred years ago, and where scholars are now in the process of digitizing thousand year old Chinese manuscripts.

A portion of the article equating print with prayer…

“The paper items preserved in the Library also shed light on the origins of another information technology: print. The Diamond Sutra, one of the most famous documents recovered from Dunhuang, was commissioned in 868 A.D., “for free distribution,” by a man named Wang Jie, who wanted to commemorate his parents. In the well-known sermon that it contains, the Buddha declares that the merit accrued from reading and reciting the sutra was worth more than a galaxy filled with jewels. In other words, reproducing scriptures, whether orally or on paper, was good for karma. Printing began as a form of prayer, the equivalent of turning a prayer wheel or slipping a note into the Western Wall in Jerusalem, but on an industrial scale.”

Recent Comments